The 1986 film Transformers: The Movie didn’t just bring my favourite transforming toys to the big screen, it changed me as well. Whereas the television series had breathed life into all of those characters, the film killed most of them off. And I loved it.

This week saw the thirtieth anniversary of the animated film Transformers: The Movie. Following two seasons of a popular children’s television series designed as a marketing tool to sell cars and planes that could transform into robots, Hasbro decided to fund a feature-length film version. Transformers: The Movie had stolen the hearts, and possibly innocence, of millions of kids long before Michael Bay failed to excite us with his recent versions, even after spending millions upon millions of pounds creating monstrously huge CGI robots that ‘whomp whomp’ed their way across screen, and then draping Megan Fox’s legs over them.

Transformers: the Movie was released in the UK on the 5th December 1986, just in time for me to ask my parents to take me and a number of my friends to see it for my eighth birthday. I remember most of us being crammed into the back of my dad’s Lada, a car that has never and will never be considered for any transformer model, but which got us there. However, that journey was one of the last of those memories of innocence, because after ninety minutes of animated action, much of my childhood would have been destroyed, trampled on and smashed to smithereens. Or at least plastic, faux metallic shards.

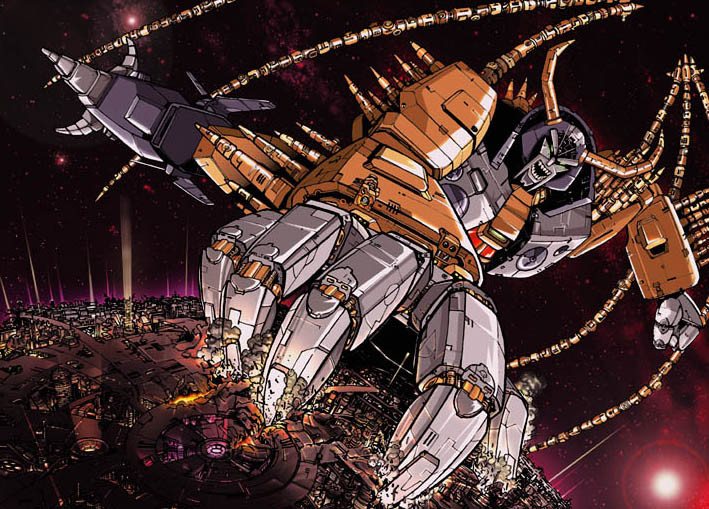

Not literally, of course. I would still have many years of frolicking, gambolling childhood and making an arse of myself ahead (I’m still going on that last one), but something had been broken in my toy-box (probably not a euphemism) that just could not be repaired. A gigantic, nigh-on invincible, planetary-sized bad guy had stomped his way through my toy collection, far more damagingly than any roughhouse play that I could imagine, brutally and unapologetically killing many of my childhood companions. Unicron had introduced me to toy mortality. His animated rampage taught me that Transformers really could die, and that that was pretty awesome.

It is perhaps necessary that I set the scene somewhat. I was eight years old, monumentally so, after having been seven years old mere days before (a gulf of time akin to dog years when you are that age). Star Wars had only recently kick-started the concept of film-related toy merchandising and the US of the 1980s had picked up that gauntlet with gusto. Toy production was rampant and line sales had become the driving force behind the creation of much of kids’ TV. Hasbro in particular were at the forefront of this sea-change, producing both the television series and product lines for GI Joe, My Little Pony and Jem, amongst others.

Although I had already begun to convert to Action Force toys at that point (not GI Joe, as the miniature, plastic pose-able military figures were named in the States), the Transformers were, for me, the best of these eighties toy-to-TV-to-toy products. It had no equal. The Gobots were a shitty, kinder-egg knock-off, Mask were a poorly conceived equivalent and the two-dimensionality and immobility of He-Man was always a disappointment. Whereas Transformers, well, they bloody transformed!

The original two generations of toys were gob-smackingly amazing, certainly to my six-year old eyes, and I remember being in awe when I first saw the Dinobots in a supermarket. Sadly, I was never to own one, although I did later (ok, admittedly, quite recently…) purchase myself an original Soundwave via ebay. The brilliance of these early Transformers was their dedication to making the vehicles look right first, and worrying about the robot version as a pragmatic secondary concern. The series’ chief villain, Megatron, is a good example, as the gun he became was brilliantly crafted, although the robot it converts into appears to be a strangely cod-pieced homunculus, and lacks every bit of the menace of its on-screen counterpart. I still want one though.

The Transformers TV series also seemed vastly superior to the other product-inspired kids’ shows of the time. I’m sure it wasn’t, especially looking back at the series itself; it was probably my nostalgia at play, and I expect that the fans of He-Man, GI Joe or My Little Pony all had similar, subjectively favourable recollections. However, for most of us, these shows were our first introduction to Japanese anime and those 1980s cartoon series were powerful and impacting, stuffed with action that felt epic, appearing to be taking place on an unprecedented scale. Toei Animation were responsible for many of these productions, however the animation took a massive leap forward when it came to producing Transformers: The Movie. With a budget of $6 million (over six times the cost of producing the equivalent ninety minutes of TV episodes) the film was completed in one year, with the Toei team working at a furious rate to deliver such an ambitious project within such an accelerated timeframe.

And it doesn’t disappoint. Well, not at the good bits anyway, although there are some scenes that are typically cheesy and cheap, for instance no-one really needed to see Autobots and Junkions dancing…

One of the joys of Transformers was their distinctiveness and individuality, and how each of the characters were clearly defined. The show’s definitively binary division of the ‘heroic Autobots’ and the ‘evil Decepticons’ is personified by Optimus Prime, voiced by Peter Cullen, who would lend a dramatic tone to the Autobot leader (and would do so again twenty years later for Michael Bay’s big screen versions) while the ‘maniacal’ Megatron was brought to life by Frank Welker, supplying a befittingly nasal but menacing bite to Prime’s Decepticon counterpart.

Welker also delivered a number of the character’s voices such as Mirage and Soundwave, including the latter’s compartmental characters Frenzy, Laserbeak, Ravage and Rumble, whose line, ‘first we crack the shell, then we crack the nuts inside!’ is still one of my favourites from the movie. Welker also provided the voice for another 80s cartoon favourite, Scooby Doo. However, my favourite of the voice actors was always Chris Latta, who primarily played the wonderfully insufferable and treacherous Starscream. Latta’s screeching mixture of ambition and cowardice, which he would replicate for GI Joe’s Cobra Commander, added a real sense of political conflict within the Decepticon ranks, and personified the inherently traitorous nature of the show’s villains.

None of these factors capture what left the 1986 film so indelibly etched into my young mindset though. What Transformers: The Movie brought was death. Glorious, brutal death, and no character was safe.

To any Game of Thrones viewers who, from series to series, are still shocked when one of their best loved characters is unceremoniously offed; you know nothing.

You have no idea what it was like to be an eight-year-old on a birthday party trip to the cinema, bearing witness as, within the first half hour, 80% of your favourite playmate characters – 80% of every fans’ collective toybox, both heroic and evil alike – were murdered in front of your eyes. It was like a Transformers apocalypse, and it was astonishing.

This cull, affected with more brutality than the third act of a Shakespearean tragedy, was not realised due to the producer’s desire to challenge their pre-adolescent audience’s notions of mortality, but as a fortunate by-product of corporate decision-making. After two successful seasons of the television cartoon series, Hasbro had exhausted their sales and decided to stop production on a vast swathe of their old lines, before ushering in the new ones. It was their surprisingly fateful decision to affect this through the big-screen obliteration of those characters in a monstrous bloodbath (or perhaps, an energonbath).

Imagine if Hasbro had decided to launch a new range of My Little Pony by making a feature film in which the evil villain Findus turns Dream Castle into an abattoir by mercilessly murdering Butterscotch, Lickety-Split and twelve of their friends…

None of this mattered to me at the time, of course, but the effect on my childhood self from watching this on-screen carnage was revelatory. Death, arriving in the form of a robotic, animated version of The Charge of The Light Brigade, had come to wipe out my toy collection. It was liberating, and the murders kept coming. The first twenty minutes of Transformers: The Movie is a ruthless experience. Character after character falls in an animated techno-gorefest as a score of beloved Autobots are either killed, with smoke pouring from their eyeballs, or summarily executed at point blank range.

The film begins ominously, as the giant, mechanical planet Unicron is introduced, bearing down on a smaller planet of benign robots before annihilating it entirely and devouring all inhabitants. Unicron is voiced by Orson Welles, in the last role he played before his death in October 1985, just five days after the final recording session. Describing the role, Welles had told his biographer ‘You know what I did this morning? I played the voice of a toy. I play a planet. I menace somebody called something-or-other. Then I’m destroyed. My plan to destroy whoever-it-is is thwarted, and I tear myself apart on the screen!’

He was not always so withering in his appraisal of the role (apparently comparing the script to King Lear in one of his more generous moments) but Michael McConnohoie did point out that ‘the irony of <Orson Welles> playing a planet-sized eating machine wasn’t lost on anyone.’ Welles was so weak by the point of recording that engineers had to heavily synthesise his voice, however, whatever his motivation and state, Welles’s last performance adds considerable weight to Unicron (no pun intended) and delivers a necessary, impressive gravitas (again, no pun intended).

Welles was not the only star talent of the time to lend their voice to the film’s robotic characters. Megatron’s evolution into Galvatron also saw Welker hand the role to the more powerful voice of Leonard Nimoy, while Judd Nelson, a freshly A-listed celebrity at that point after The Breakfast Club, played the young Autobot hero Hot Rod. Eric Idle provided some ‘comedy’ by voicing the television-addled Wreck-Gar and Scatman Cruthers, also in his last job before his death, reprised his series role as Jazz.

Despite these days being considered a firm cult classic, Transformers: The Movie was a commercial failure, leading to the decision not to make the proposed GI Joe movie a theatrical release but send it straight to video, as well as the cancellation of a planned Jem film. Furthermore, so traumatising was the death of so many characters to some young viewers that Hasbro also decided not to kill the GI Joe character Duke, as they had planned, but instead place him in a coma.

I feel that this is a shame. Transformers: The Movie was such an eye-opening experience that this reversion to timidity, to me, showed a failure on Hasbro’s part to understand that what they had unwittingly unleashed was far more memorable and impressive than anything they could have planned.

It was time for those of us watching to move on from those toys and kid’s shows anyway, and wiping them out was a bold and cathartic method to achieve this.

Even if I hadn’t already been growing out of the franchise, the next generation of toys were underwhelming. Advances in plastic production technologies meant that they were produced cheaper, but subsequently also felt cheaper, and were less innovative in design. Springer was an acceptable addition, turning into both a helicopter and a tank-thing but the toy of Hot Rod was gaudy, while Arcee (the first female Transformer) and Kup, being Cybertronian Autobots, didn’t actually turn into anything. It was over.

I am a better person for the brutal farewell the film provided me. It was the satisfying finality of Breaking Bad. Or the Sopranos finale, without the ambiguity. For all their epic scale and the awe-inspiring amount of on-screen action in Michael Bay’s films, those movies barely registered with me in any gripping, involved way. They fail to inject any real depth into his remade characters, and the few Autobot deaths we see across the film struggle to draw any kind of emotive reaction other than a slight sense of wastefulness.

There was no waste in Transformers: The Movie (excluding, of course, on the plant of Junk). After the initial onslaught, the film hurtles through the next hour with Unicron closing in on Cybertron while the Autobots race to save themselves and their planet, all fuelled by Vince DiCola’s cheesy 80s ‘synth-based hard-driving metal’ soundtrack. I don’t even know what most of those words mean, it’s certainly not my kind of music but it does now own a place in my memory and, more embarrassingly, my music collection. Everyone, even first-time (and most likely pretty unimpressed) viewers, gets a bit fired up when Optimus Prime goes on a Decepticon-smashing rampage to Stan Bush’s The Touch, but for those who were there in the cinema in 1986, it’s a nostalgia trigger of Proustian proportions. The dialogue was solid in general, and epically dramatic when it needed to be, ‘One shall stand, and one shall fall.’ Some of the quotes still delight me today, such as Rumble’s ‘Nobody calls Soundwave unchrasimatic!’

However, most importantly, every time I watch Transformers: The Movie, I am in awe at the boldness of staging such a brutal massacre as the starting point of a big screen film. One based on a cartoon, designed to sell toys that were pitched to a demographic of seven to twelve-year olds.

It was wonderful destruction, both on-screen and in my mind. Transformers: The Movie, for or because of all its flaws and clunkiness, resonated with me when I was eight years old, and I still love it thirty years later.