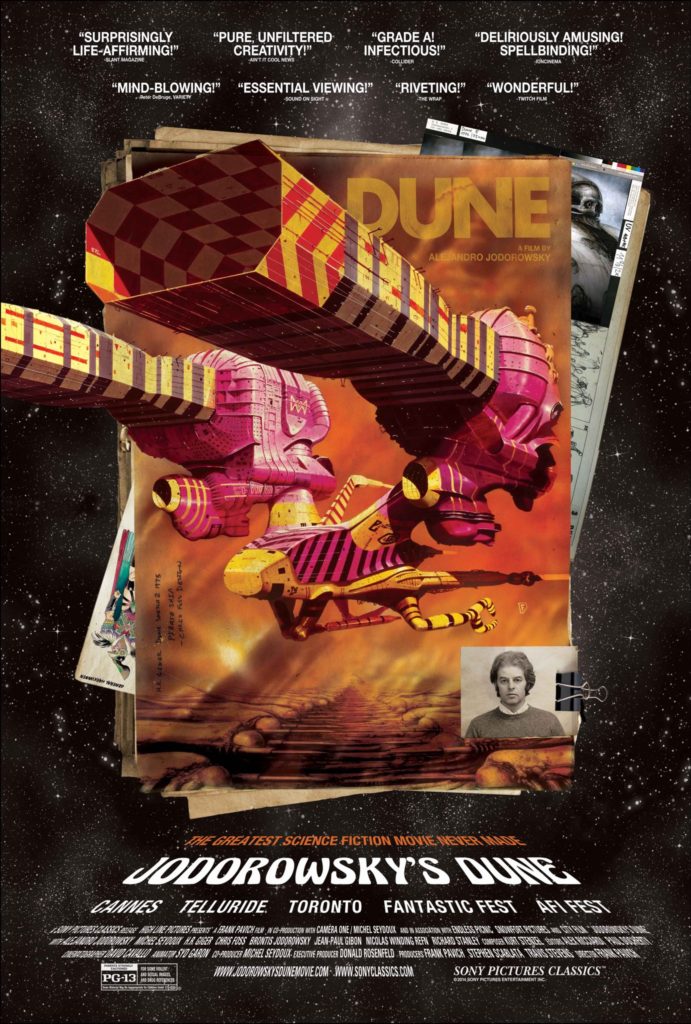

Last year’s Cannes Film Festival saw the release of Jodorowsky’s Dune, a documentary outlining the Chilean director Alejandro Jodorowsky’s ultimately doomed attempt in 1974 to realise his distinctive vision of Frank Herbert’s science fiction epic. We follow the director as he assembles an outrageously impressive group of collaborators, ranging from HR Giger to Pink Floyd and Salvador Dali, as they began to build what many have called ‘the greatest science fiction film never made’.

As a fan of Frank Herbert’s series of novels, I am still waiting for a definitive, or even sufficient, adaptation of Dune which succeeds in capturing the scope and complexity of the original books. The reason that this has not yet been achieved may lie in that same complexity, and the complications of translating it to the big, or small screen. The four original novels are based twenty thousand years in the future, and collectively span forty thousand years of galactic politics and war. It is a work and universe as full and far-reaching as Tolkien’s Middle Earth, and it took sixty years before Peter Jackson was able to produce an acceptably impressive representation of The Lord of the Rings.

The project, after Jodorowsky’s had been pulled, was eventually given to David Lynch, who was at that time enjoying the pinnacle of his directorial respect. Jodorowsky himself begrudgingly professed that, after him, Lynch was ‘the only one in this moment who can do it’. However, Lynch’s Dune was terrible. Plagued by studio interference and budget cutbacks, he eventually withdrew his name from the production credits, effectively disowning it. In order to compress the film to one and a half hours, it relied heavily on exposition, with the use of internal dialogues and extraneous characters (to this version at least) giving lengthy explanations of political movements, and the final half hour is so crammed that planetary actions hurtle by at breakneck pace. There are some elements of David Lynch which shine through in the form of dark, hulking set pieces but they are few and far between and the production is otherwise only lifted above the mediocre by a few fine performances, Ian McMillan’s monstrous Baron Harkonnen in particular. For a movie so short, it is flat, lumbering and emotionless.

The project, after Jodorowsky’s had been pulled, was eventually given to David Lynch, who was at that time enjoying the pinnacle of his directorial respect. Jodorowsky himself begrudgingly professed that, after him, Lynch was ‘the only one in this moment who can do it’. However, Lynch’s Dune was terrible. Plagued by studio interference and budget cutbacks, he eventually withdrew his name from the production credits, effectively disowning it. In order to compress the film to one and a half hours, it relied heavily on exposition, with the use of internal dialogues and extraneous characters (to this version at least) giving lengthy explanations of political movements, and the final half hour is so crammed that planetary actions hurtle by at breakneck pace. There are some elements of David Lynch which shine through in the form of dark, hulking set pieces but they are few and far between and the production is otherwise only lifted above the mediocre by a few fine performances, Ian McMillan’s monstrous Baron Harkonnen in particular. For a movie so short, it is flat, lumbering and emotionless.

The proposed film that Dune’s Jodorowsky documents would have been anything but. At the height of the seventies, Jodorowsky, an unencumbered surrealist, describes how his aim was to create a film experience to rival taking LSD; a hallucinatory and spiritually transformative awakening akin to ‘the coming of a God’. Whereas Lynch would employ his distinctive use of darkness and shadow, Jodorowsky would assault the viewer with vibrant colour and diversity, deserts of visceral orange and vibrant blues. It is his uninhibited spiritual optimism, ambition and energy that carries the documentary, much as it must have been that energy which enabled him to assemble his ‘prophets’, the astounding array of talent involved in pre-production.

The cast and crew were staggering and the acting talent diverse and impressive. Magma and Pink Floyd would produce the distinctive music specific to each race, while David Carradine was set to play Duke Leto Atreides, Mick Jagger for Feyd Rautha and Orson Welles was on board to portray the gargantuan Baron Harkonnen. Jodorowsky had even secured the services of Salvador Dali to be the Galactic Emperor, Shadam Corrino IV, through the promise of ego-nourishing extravagance ($100k per minute, making him the highest paid actor in Hollywood, though he would only appear for four minutes in total) and games of surrealist one-upmanship.

The cast and crew were staggering and the acting talent diverse and impressive. Magma and Pink Floyd would produce the distinctive music specific to each race, while David Carradine was set to play Duke Leto Atreides, Mick Jagger for Feyd Rautha and Orson Welles was on board to portray the gargantuan Baron Harkonnen. Jodorowsky had even secured the services of Salvador Dali to be the Galactic Emperor, Shadam Corrino IV, through the promise of ego-nourishing extravagance ($100k per minute, making him the highest paid actor in Hollywood, though he would only appear for four minutes in total) and games of surrealist one-upmanship.

The aesthetic design of the Dune universe was meticulously planned. Sci-fi artist Chris Foss and HR Giger would design much of the landscape, cultures and technologies. Traces of the distinctive work the pair produced, Foss defining the sumptuous Atreides and Giger the brutal, darker-toned Harkonnen, can be found in their later works. The now iconic Giger was, at this point, unknown in the film world, and would later renew his partnership with the film’s special effects director Dan O’Bannon to create Alien.

The bulk of the film’s storyboard was produced with Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud, and this remarkable body of work is brought to life, to great effect, in the animated depictions which punctuate the interviews and give the documentary an absorbing and distinctive style.

The project finally met its demise as the Hollywood studios, although impressed by the technical and production talent, scale, economy, craft and artistry of the project, would still all reject it, on the grounds of their mistrust of the maverick director and his unwillingness to compromise on the film’s length, the same constraint that would later topple Lynch’s project. Jodorowsky recounts the point when he was reluctantly dragged to see Lynch’s production, telling how the fear of his vision being perfected by another faded as, moment by moment, he came to the joyously human realisation that it was ‘awful’, but immediately spotting where the fault lay ‘David Lynch is an artist…this is the Producer’.

The most accurate representation of the books is the 2006 Sci-Fi Channel television series, but it does so at the expense of all emotion and the higher concepts of eugenics, power and spirituality of the original. The film that Jodorowsky’s prophets attempted to make would have strayed further from the core text than Lynch’s, Jodorowsky himself admitting that changing the ending of the book, as his production planned to do, was akin to ‘raping Frank Herbert’ (although ‘with love’) but it would surely have been worth it. Jodorowsky’s Dune is heart-wrenching as a Dune fan because it is a tale of what could have been. The life that the documentary breathes into the failed project has so much vivacity and passion that it only makes its loss all the more moving.

Remarkably, it is Jodorowsky’s positivity and resilience, in the face of the crushing demise of his dream, which permeates the experience of Jodorowsy’s Dune, endowing it with a sense of hope, rather than regret. His boundless spirit to create, unbowed and unconstrained, proved a bewitching match to giants of the time like Pink Floyd, Orson Welles and Salvador Dali. His ambition and unrestrained belief are honestly inspirational and remains with you after viewing. It makes you want to unearth that dusty screenplay, and do it properly this time. To be like Jodorowsky and insist that your work must ‘have heart, have ambition … why not? Why not!?’

Why not indeed?